Pangolins are small mammals that only move around at night. Hardly a zoo has been able to keep one alive. And yet, they sit above the elephant and rhino as the most illegally trafficked animal in the world.

Pangolins are amazing: With shiny scales and pointy heads, they look like miniature dinosaurs; baby pangolins ride around on their mothers’ tails; they slurp ants with 25cm-long tongues; and they can curl up into an armoured ball that foxes any predator – except humans. Being so elusive, not much more is known about them.

Pangolin researchers meeting in January 2017 in Singapore concluded that increased demand from China for pangolins has led to "great declines" in populations across Cambodia, Viet Nam, and Laos.

“Pangolins have been used in traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years, but growing human populations and greater wealth across China have increased demand,” says the Worldwatch Institute. “Pangolin fetuses, scales, and blood are used in medicine, the meat is considered a delicacy, and stuffed pangolins are sold as souvenirs.”

All eight (four Asian and four African) species of pangolins are now prohibited from international trade thanks to greater protections they won at the 2017 conference of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which UN Environment hosts.

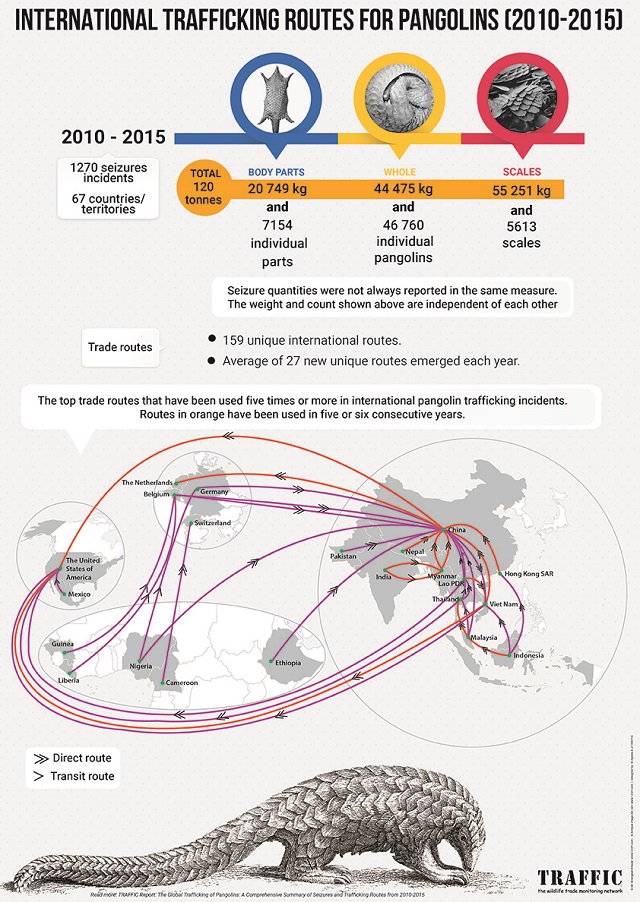

However, new research based on cross-border pangolin seizures shows that a combined minimum of 120 tons of whole pangolins, parts and scales were confiscated by law enforcement agencies from 2010 to 2015. On average pangolins weigh about 5 kilograms, so that’s a lot of pangolins.

The research was published in December 2017 by TRAFFIC and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and titled The Global Trafficking Of Pangolins: A comprehensive summary of seizures and trafficking routes from 2010–2015. It highlighted the truly global nature of the trade: 67 countries/territories were implicated, including those not home to pangolins.

Smugglers were said to be using 27 new global trade routes, and Europe (especially Germany and Belgium) was identified as a major transit hub, mostly for African pangolins being transported to Asia. However, the Netherlands was reported as a destination for large-quantity shipments of body parts and scales from China and Uganda, respectively.

The report’s findings underscore the highly mobile nature of smuggling networks, with traffickers quickly shifting from commonly used routes after a short period and creating many new routes each year to evade enforcement efforts.

17 February is World Pangolin Day. Find out how the UN’s Wild for Life campaign is working to protect pangolins and other species threatened by the illegal wildlife trade.

The Environmental Investigation Agency says there has been a significant growth in the trade of African pangolin species, especially for scales, in the last few years.

In November 2017, China announced the seizure of 11.9 tons of scales from a ship in Shenzen, the world’s largest ever pangolin seizure.

“This report shows that while enforcement efforts are absolutely critical, we must give as much priority to tackling the demand that drives illegal trade,” says UN Environment wildlife communication expert Lisa Rolls.

“World Pangolin Day on 17 February is an important awareness-raising moment. We need to get the word out there to educate consumers who may not be informed about the impacts of their purchases and to try and prevent new users. We are asking people to join the Wild for Life campaign for Pangolin Day and spread the word!”

For further information: Lisa.Rolls[at]un.org